Deploying Cloud Run with Service YAML

Declarative, source-controllable configuration

Automated deployments and continuous delivery always has a bit of an open-world video game feel to it. There are many different ways one can deploy a piece of software and at times it feels like there’s no right or wrong way, just your preferred one.

The whole “DevOps” engineering topic has been a favourite lately. This is not influenced only by the construction of this blog. It is also influenced by my work as a data engineer over the last two years. There is an argument that “DevOps” in itself shouldn’t really be the term for someone’s role. Maybe that’s right, but it has been co-opted over time in the same way that software “engineers” stole that label from the real engineers out there, and the word “literally” doesn’t mean “literally” anymore. That’s an argument for another day.

In my data engineering work, I have largely used shell commands in CI/CD runners to get my deployments done. These are usually interacting with cloud CLIs, building Docker images, running unit tests, etc. These work fine, but I’m sure everyone reading this knows of the pain of getting shell commands exactly right.

In some cases, there’s a better way. This post will show how to keep declarative, version-controlled configuration files to deploy Cloud Run services, and how to use them in your CI/CD pipelines.

The setup

My reference repository is here. It is a straightforward, simple URL shortening API written in Go, another recent favourite. I did this project for practice developing in Go, as well as a few other components:

- Infrastructure as code using OpenTofu

- Serverless compute using Cloud Run

- NoSQL database using Cloud Firestore

- Automated deployments using Github Actions to tie it all together.

The deployments also cover GCP Workload Identity Federation, which I covered in a previous blog.

When deploying a Cloud Run service, a few things need to be specified:

- The service account the service will run under

- The container image to deploy

- The project and region to deploy to

- The name of the service itself.

Note: My pipeline is deployed by one service account, while being invoked by another. The executor account requires the “Cloud Run Invoker” role, and the deployment service account requires “Cloud Run Admin”.

To finish setting the scene, my service needs a few extra variables set on deploy:

- The project ID

- The Firestore database ID to connect to

- The domain name being served.

Cloud Run deployments - the old way

If you’ve followed this blog for a while, you may have already seen part 2 of building the blog, which covered similar ground.

To deploy my service to Cloud Run via the CLI, I would likely do something like this - from my old repo:

This works, is totally fine, and how most demos/tutorials/blogs will show you how to do things.

Cloud Run deployments - the new way

Cloud Run is a managed version of an open-source framework called KNative. This in itself is a managed layer on top of Kubernetes. Together, they form a powerful serverless framework that abstracts away all the hard work and leaves you to simply deploy a container.

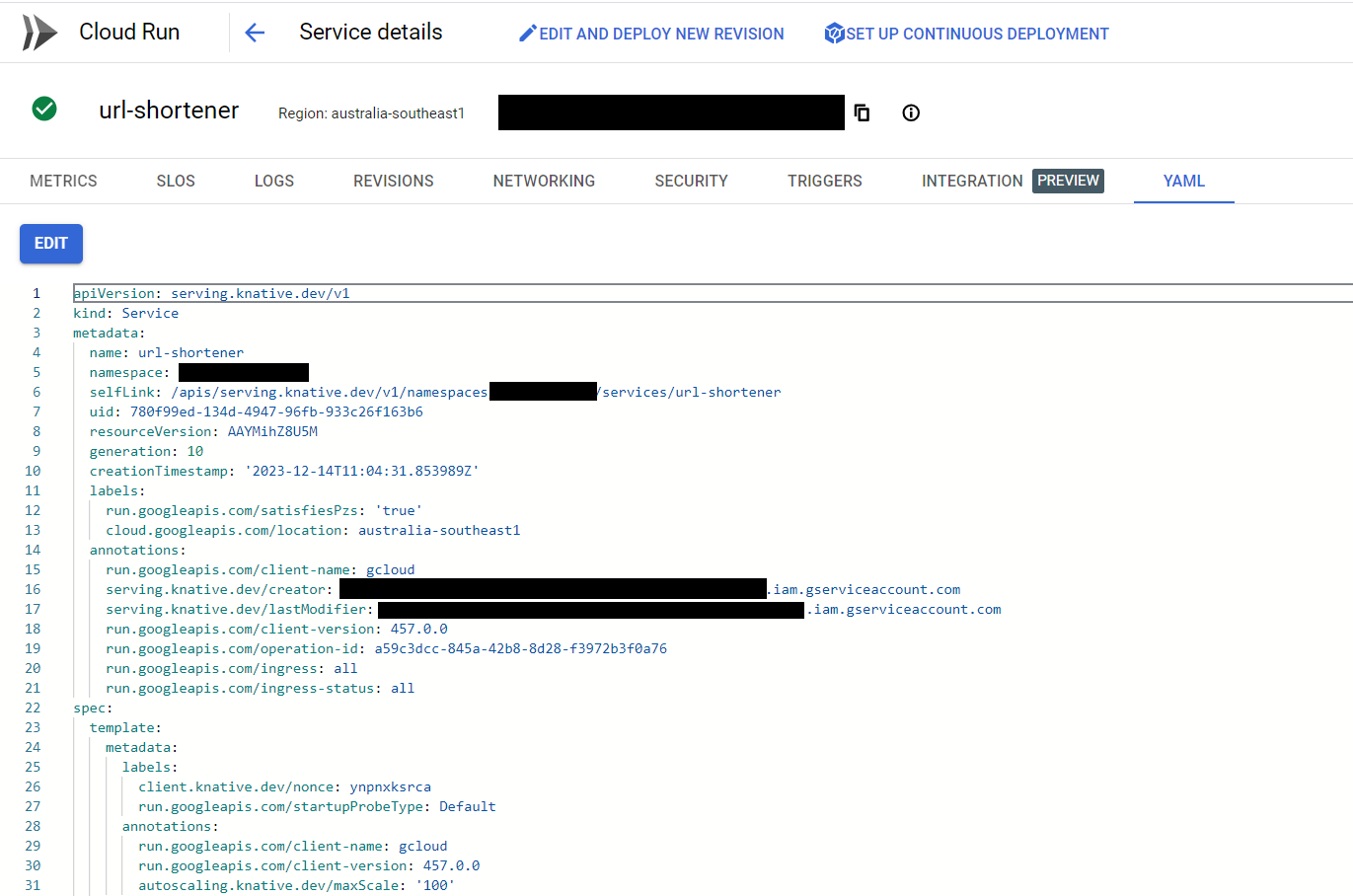

However, the upside of its roots is that we can specify a Kubernetes-style service YAML file to declaratively configure our service.

The full specification for the YAML can be found here, but a simpler snippet is in the deployment guide for Cloud Run here.

This can be a bit much to wade through, so I recommend learning the same way I did: deploying your Cloud Run service in a development environment using either GCP UI or CLI, then pulling the auto-generated YAML file it creates and editing that to your heart’s content.

This is the full YAML file as it sits now in my URL shortener’s repository.

Deploying in a CI/CD pipeline

My YAML file specifies all the settings you’d require for a Cloud Run service - % of traffic allocation to the service, resource limits for CPU and memory, timeouts, etc. Of note are the placeholder values for the configuration items listed earlier in this post.

These values are all placeholders surrounded by angle brackets (<>). They are not known before deploy time, and are injected into the container by this service’s CI/CD pipeline. The trick to this is our trusty Unix tool sed.

The full Github workflow is publicly available here, but I’ll focus on the deployment steps.

The first step of this excerpt uses sed to do global replaces of the placeholder values with secrets stored in my Github repository. Each sed call pipes its output into the next call, and the final result is output to a service.yaml file. There are no real surprises here - I have gone into detail about using Github secrets in examples during my posts on building this blog. I generally set the secrets up as environment variables for the workflow, which is why they are referenced with the env prefix instead of secrets.

I think there are ways to reduce the code in the pipeline even more:

sedhas a-eswitch to allow multiple commands to run at once, instead of my pipe (|) method- Moving some of these longer commands to a shell script might make things a bit cleaner. DevOps people - let me know if you do or don’t like this idea!

It is also possible to link secrets in GCP’s secret manager to the container using similar YAML. The below example would be used if I wanted my DATABASE_ID environment variable to be pulled from secret manager. The “key” is actually the version of the secret you want - this can be a number, or just the latest value.

The only gotcha here is my DOMAIN_NAME environment variable. The domain name is needed to prefix any shortened URLs with the domain the service is running from. It is not known at service deploy time, unless you have bought a domain for the service and know what to put in here ahead of time. I don’t, so I’m using a little trick: use gcloud run services describe to get my newly-deployed service’s URL, and use gcloud run services update to inject a new environment variable into the container.

This same approach can also be used for Cloud Run Jobs - my first production use of this method was done with a Job, with no issues. The full reference is here in case you are interested - some of the static configuration values need to be slightly different.

In any case, this approach offers a declarative way of deploying your service configuration. To me, it feels a bit cleaner - source controlled in a separate section of your repository, not getting lost in all the other script commands in a CI/CD pipeline.

Back in my site deployment blogs, I noted that since I had a comma-separated list of allowed hosts for Django, I had to specify a substitute delimiter for my environment variables at deploy time. This approach would have avoided having to do this. It is slightly more complex than just writing your deploy scripts in the Github workflow, but I think over time it will pay off with a more understandable code base and a smaller blast radius if you need to make changes.

Finally, Google seems to endorse this method via a YouTube video here. It doesn’t cover some pieces of this blog, but it is still worth watching for a section on canary deployments.

I hope this has been useful. Feel free to contact me on LinkedIn if you have any questions/suggestions, or you have a better way for me to inject my domain name into my container.

Thanks for reading.